Losing The Thread | Textiles

India's textile sector has a long way to go before it achieves economies of scale to challenge China's dominance in world markets.

Once dubbed 'Manchester of the East', the textile town of Bhiwandi in Thane district, 40 km north of Mumbai, is today reeling under competition from the 25-30 per cent cheaper Chinese fabric. Ask Sharadram Sejpal, 58, a powerloom owner here and spokesperson of the Bhiwandi Powerloom Association, why they can't match Chinese pricing and he says: "Electricity is costlier here and taxes are high." Ironically, 90 per cent of the powerlooms in India are cheap imports from China.

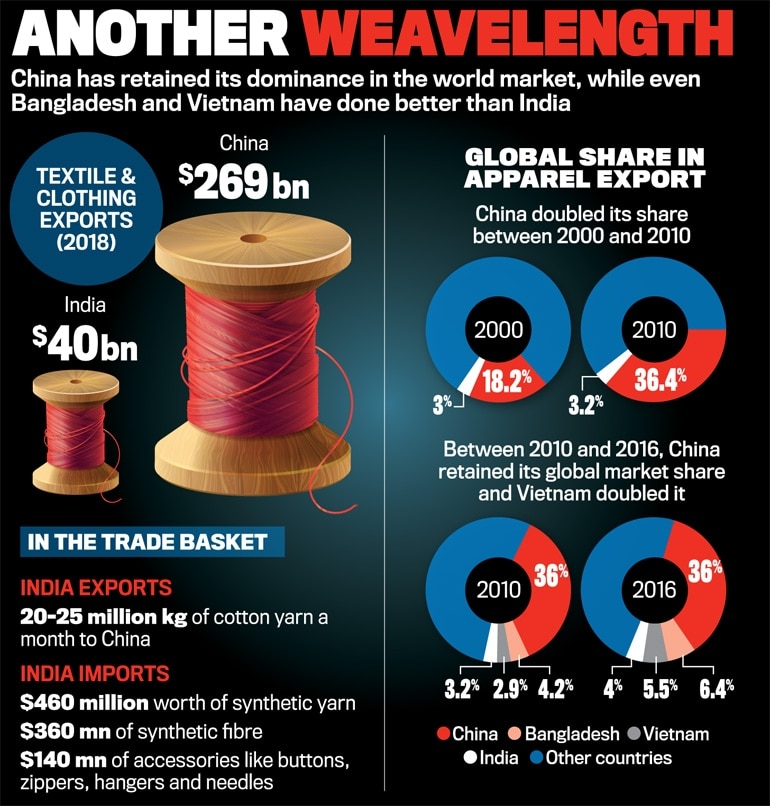

Over and above the cheap looms that sustain small loom owners such as Sejpal, India is dependent on China right across the entire textile value chain, starting with raw materials for textile production, the synthetic yarn, the fabric and even the final product, be it garments or home textiles. China is India's fourth largest trading partner in purified terephthalic acid (PTA), which goes into making polyester fabric, and the largest trading partner in polyester staple fibre (PSF), made using PTA as one of the inputs. In 2019, China exported around 41,000 tonnes of PTA to India. India imports $460 million worth of synthetic yarn mills used to make fabric and $360 million worth of synthetic or man-made fabric from China annually. It also imports over $140 million worth of accessories like buttons, zippers, hangers and needles. In February this year, the Centre removed anti-dumping duty-ranging from $27 to $160 per tonne-imposed earlier on PTA imports from China and other countries after the textile industry asked for it to reduce production cost and enhance global competitiveness. This would have been a further boost to PTA imports from China but for the Covid-19 pandemic, which brought all industrial activity to a near-standstill.

Source: Commerce ministry; Cotton Textile Export Promotion Council; Clothing Manufacturers Asscn of India (Gaphic by Tanmoy Chakraborty)

On the garments front, though China is the world's largest exporter, when it comes to India, it is allegedly indulging in back-handed practices and routing garments through Bangladesh into the country. Chinese fabric is going into Bangladesh, being converted into garments and exported to India. These are 15-20 per cent cheaper than Indian garments. Bangladesh exported $499.09 million worth of garments to India in 2018-19. Indian fabric too goes to Bangladesh, is made into garments, and exported back to India, but in much smaller numbers than Chinese exports via Bangladesh. India also ships 20-25 million kg of cotton yarn a month to China, which is converted into cotton fabric and exported to other countries such as Bangladesh to be made into finished garments.

However, even as China constitutes an important trading partner for India, its exports to India are a fraction of its global exports. Of the $20 billion worth of PSF China exported worldwide in 2018, India had just a 3.8 per cent share. Its PTA exports to India were just about 6 per cent of its total exports of the commodity worldwide. China exported $151.37 billion in readymade garments and clothing accessories globally in 2019, so its exports to India in that category (routed through Bangladesh, as alleged) are just about 3 per cent of its global sales. The balance of trade is also clearly in China's favour. In 2018, India imported $3.46 billion worth of textiles and clothing from China. However, its exports of textiles and apparel to China in the same year were a little over half that, at $1.8 billion.

Textiles is one of India's oldest industries, contributes 2 per cent to GDP, employs about 45 million people and contributed 15 per cent to India's export earnings in 2018-19. Globally, India ranks second in textile exports, with a 6 per cent share, and fifth in apparel exports, with a 4 per cent share. The country also has the second-largest vertically integrated textiles production base in the world after China. Yet, despite its many advantages, Indian productivity, technology and products lag far behind China's or even of countries such as Bangladesh and Vietnam, who have built their capabilities fairly recently. India's textile and garment exports of $40 billion are small compared with China's $269 billion in 2018. Between 2000 and 2010, China doubled its share in global apparel export from 18.2 per cent to 36.4 per cent, while India's share went up from a mere 3 per cent to 3.2 per cent. Another six years from then, China retained its global market share, Bangladesh increased it from 4.2 per cent to 6.4 per cent, Vietnam from 2.9 to 5.5 per cent, but India inched up from 3.2 to 4 per cent. This is because the apparel export sector in India is largely composed of small and medium enterprises that lack pricing power, access to cheap credit and technical knowhow.

To attract big manufacturers to Surat, the Union minister for textiles Smriti Irani visited the textile town this January to initiate the process of developing it as a textile machinery hub that could provide affordable state-of-the-art technology. Textile units in Surat currently depend on machinery imported from China, Korea and Germany. But efforts such as these look piecemeal when compared to the integrated approach countries like China follow. In India, the major components of the textile business-the making of cotton or synthetic yarn or thread, the looms where the yarn is made into cloth, the printing and dyeing and later the garment-making-are scattered across the country, making logistics cumbersome and the cost of production high. China, on the other hand, has created clusters, saving on costs and enabling easy movement of goods across the supply chain. The textiles sector in India is beset by underproductivity, outdated machinery and a distorted duty structure that encourages import of high-value apparel instead of raw cloth that can be turned into value-added garments for the international market. Wages, too, have been on the rise in India, adding to costs. Moreover, India continues to focus on cotton fabric when the world is moving toward man-made fibre that is both convenient and cost-effective.

We also lack a brand image in the international market, says Kumar Doraiswamy, CEO of the Tiruppur-based Eastern Global Clothing company. Tiruppur, which exports garments worth Rs 26,000 crore a year, had already been reeling from the bankruptcies filed by retail giants in the past year when Covid-19 struck and the country went into a lockdown, with none of the factories managing to resume production at full capacity. However, as Raja Shanmugam, president of the Tiruppur Exporters' Association, points out: "While we were shut, China was ready to supply to the world." Its factories were up and running, moving in to capture the potential market for personal protection equipment kits. We, on the other hand, have failed to capitalise on the prevailing anti-China sentiment globally.

India has a window of opportunity to expand exports of readymade garments, but neither we nor other countries potentially have the scale or size to take material advantage of the opportunity available due to disruption in Chinese supplies, according to Hetal Gandhi, director at Crisil Research. Moreover, countries such as Bangladesh, Vietnam and Pakistan have free trade agreements with the European Union, which means their goods attract zero duty while India pays 9 per cent. "We have a cost disadvantage," says Gandhi. Shutting down big retailers will also have a significant impact. According to Crisil estimates, FY21 could see a 30-35 per cent drop in readymade garment exports.

When it comes to garments, China can produce in 45 days what India takes a year to produce, says Rahul Mehta, president of the Clothing Manufacturers Association of India (CMAI). "For the past four years, our export growth has remained static," he says. The Covid lockdown may have brought exports to a complete halt, but introduction of the Goods & Services Tax in July 2017 had slowed down exports significantly, Mehta adds. While cotton fabric, made from cotton yarn, attracted GST of 5 per cent, it was 18 per cent for man-made synthetic fibre; silk and jute are totally exempted from GST purview. GST rates on apparel, too, vary, with apparel below Rs 1,000 attracting a GST of 5 per cent, and the rest 12 per cent.

China also has huge economies of scale while India's focus is on smaller orders in smaller quantities, requiring smaller production factories. Indian productivity per tailor or machine is also much lower than its competitors'. A majority of India's factories are in the small and medium scale range, from 50 to 500 or, at a stretch, 1,000 machines. In China, Bangladesh or Vietnam, even a 1,000-machine factory is considered small. Besides, India has been focusing only on cotton casual wear, when formal winter wear, sportswear and specialty garments are a huge market.

A STITCH IN TIME: Doraiswamy at his textile factory in Tiruppur, Tamil Nadu (Photo: Shakthivel)

"There cannot be a 100 per cent shift (from China), but we have a good chance of getting some spillover from their factories," says Mehta. Some companies want to shift a part of their garments business to India, but seem to lack confidence in the business environment, especially the uncertainties surrounding the lockdown. Industry is still unsure about opening up in the hotspots of Mumbai, Delhi, Chennai and Ahmedabad, which are large markets for the business and also the worst hit. Business does not have much hope from the government, which they feel either doesn't have the funds or the inclination to extend any, although it did announce some credit-linked succour to MSMEs as part of a Rs 20.06 lakh crore Covid relief package in May. What companies want, though, is not easier access to credit but a restructuring of loans, which is the RBI's remit.

Meanwhile, textile secretary Ravi Capoor says "the Rebate of State and Central Taxes and Levies Scheme to assist exporters is extended. To offset disadvantages faced by industry players vis-à-vis countries that have zero duty charges in big/ thriving markets, this ministry is proposing schemes such as MITRA (Mega Integrated Textiles Region & Apparel) Parks and FPIS (Focus Product Incentive Scheme)".

Even as anti-China sentiment rises across the world, it is far too integrated with the world economy to be ignored. And for all the calls of boycott of Chinese goods in the wake of the current border hostilities and the push for Atmanirbhar Bharat, it's a task easier said than done. "There is a certain amount of consumer emotion in favour of atmanirbharta," says Mehta. "But building self-reliance cannot happen overnight. We also have to see if it can be sustained and the alternative products available. It's a long-drawn process."

No comments:

Post a Comment